The Cultural Path as a privileged tool for dialogue

If there is one scholar who knows the archival collection of the Custody of the Holy Land by heart, it is undoubtedly him. Professor Bartolomeo Pirone, translator and scholar of numerous manuscripts, has intertwined his life with the Arab world and the Custody. He began studying Arabic in 1955 at the Franciscan Seraphic College in Rome, later continuing his formation in Bethlehem. After graduating from the University of Naples “L’Orientale,” he taught Arabic at the Universities of Naples and Bari, collaborating with the Franciscan Center for Oriental Studies in Cairo (Muski) and with Edizioni Terra Santa.

“In 1980, Father Bellarmino Bagatti introduced me to Arabic-Christian literature, alongside my study of classical and contemporary Arabic literature. Since then, I have devoted myself steadily to this field and have collaborated with the Franciscans—today especially with Friar Eduardo, the current archivist,” Professor Pirone shares. He then lists, through recent history, the Franciscans who worked on the translation of numerous firmans, from Girolamo Golubovich to Norberto Ricciani, including Félix Sciad. A firman is an official decree issued by a sovereign authority in the legal-administrative sphere.

The Identity Card of the Custody

Friar Eduardo Masseo Gutiérrez Jiménez, a Mexican missionary, has been responsible for the Custodial Archive for one year. He holds a doctorate in Church History and, during his time in Rome, also obtained a diploma in Archival Science, Diplomatics, and Paleography in preparation for caring for the Archive of the Custody of the Holy Land. He offers us an overview of the firmans.

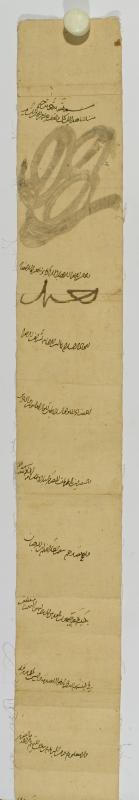

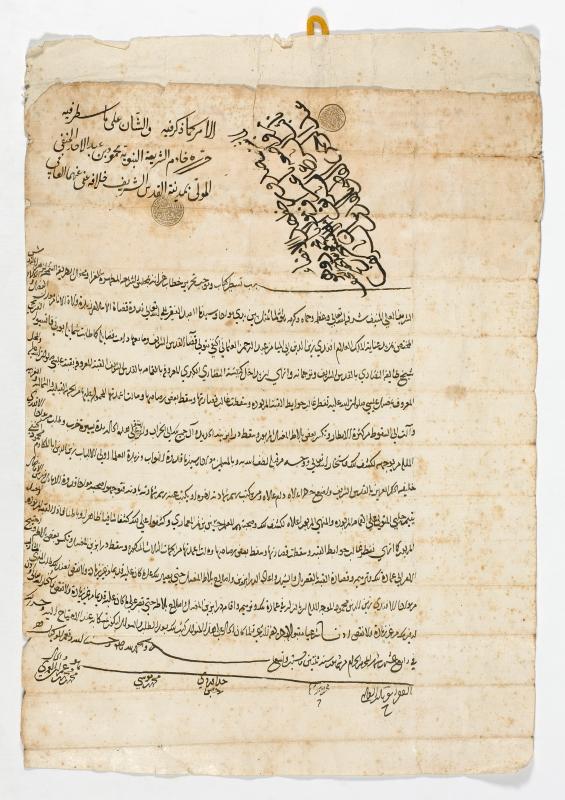

“The number of Ottoman documents is significantly higher than that of the Mamluk documents. The latter are estimated at around 500–600. The Ottoman documents, on the other hand, number approximately 2,500, if not more. It is also important to distinguish between two types of documentation in the Ottoman period: on the one hand, documents produced directly by the Sultan and the Sublime Porte, written in Ottoman Turkish; on the other, those issued by the High Court of Jerusalem, written in Arabic.”

“These manuscripts represent a true identity card of the institution, as they accompany its historical development. They document the acquisition and management of shrines and holy places, formally owned by the Holy See but situated within a complex context, also marked by interactions with other local Christian communities—Orthodox, Greek, Armenian, Ethiopian, and Coptic,” Professor Pirone explains.

At the Service of Interreligious Dialogue

“Thanks to the Terra Sancta Museum, some manuscripts have been restored in preparation for future exhibitions. Overall, around five or six documents have been restored as part of these initiatives,” Eduardo stated.

In the Art & History Museum, facsimiles of three firmans—Mamluk and Ottoman—and one Ottoman hujja (a legal document drawn up by an Islamic judge) authorizing the restoration of the dome of the Holy Sepulchre and the Stone of Unction will be displayed. The facsimile of the Mamluk firman shown in the photo will be placed in Room 7, “Foundation of the Custody of the Holy Land,” and the Ottoman hujja in Room 8, “Guarding the Holy Places,” as it establishes the legal presence of the Franciscans and their relations with authority in the holy sites. In addition to these, other documents from the same periods will also be exhibited in the museum.

There is no doubt that these handwritten works will attract the attention of future museum visitors, as demonstrated by the recent visit of the Al-Aqsa scientific delegation in October 2025. During their visit, they were deeply impressed by our preservation system, established by the Custody from the very creation of the archive. They contacted us through the Custodial Secretary and expressed interest in collaboration, especially since many of the documents we preserve were originally produced at their own institution.

“This visit was welcomed with great interest, and they particularly appreciated our document preservation system. They also expressed interest in possible collaboration; many of the documents preserved in the Archive of the Custody were in fact issued at Al-Aqsa, just as complementary materials exist in the archives of Al-Aqsa and in the State Archives of Constantinople. Comparing these sources and establishing archival collaboration are fundamental from both a scientific and historical perspective. For this reason, I hope to return the visit soon, ideally together with Professor Pirone [who was the first Christian to study Islamic Sciences at Al-Aqsa for an entire year on behalf of the Custody]. I firmly believe that the culture and heritage we preserve do not strictly belong to us: we are heirs and stewards, and our task is to pass them on to future generations in better condition than we received them. Culture opens doors: this is why awareness that sharing this heritage is a shared responsibility and a common vision is essential,” Friar Eduardo concludes.