The Georgian capital of St Saviour : new evidence of the history of the siege of the Custody of the Holy Land

The month of July 2021 will without a doubt mark the history of the building of the Terra Sancta Museum for a long time. As the main structural work was being continued in what will soon be the future historical section of the museum, medieval remains were brought to the light in the walls. Two of these, a capital and a column, send us half a millennium back in time, when the Georgians were present in these places.

If the Georgian past of the St Saviour Convent in Jerusalem is well documented today, their actual material remains are few and far between. Completely included in the brickwork of a wall, invisible for decades on end, it was by chance that these architectural remains appeared when the architects were preparing to demolish the wall.

The reuse of this material in more recent building could have shown a concern for economy and “recycling” over the different phases of the convent’s construction, but today this discovery only remains the second known occurrence of reuse. Either because the other remains were deemed too badly damaged or quite simply because the preference was to build totally new, this discovery turns out to be all the more precious as it is unique (could we say by accident?) in the history of the building.

How were these remains identified?

Research by Friar Eugenio Alliata, director of the archaeological section of the Terra Sancta Museum, attributes a Georgian origin, and more particularly ecclesiastical, to this column base and capital.

The first, and most striking clue, remains the cross sculpted on two opposite sides of the capital. Typically Georgian, it has been found in particular on the Georgian national flag since 2004 and is believed to originate from the Sion of Bolnissi, a Georgian church of the 5th century. This same cross can be seen in a second place in St Saviour : in St Helena’s courtyard where another example of reusing sculpted stone can be seen, decorating the top of the windows.

At this stage, in order to have an idea of the exact building these remains belong to, the previous presence of the Georgian church of St John the Evangelist, more or less in the same spot as the demolished wall, must be recalled. Caution is necessary however, because if the hypothesis of this church as the place of origin of these remains is the most likely, it must not be forgotten that at the time there were numerous other Georgian churches in the neighbourhood.

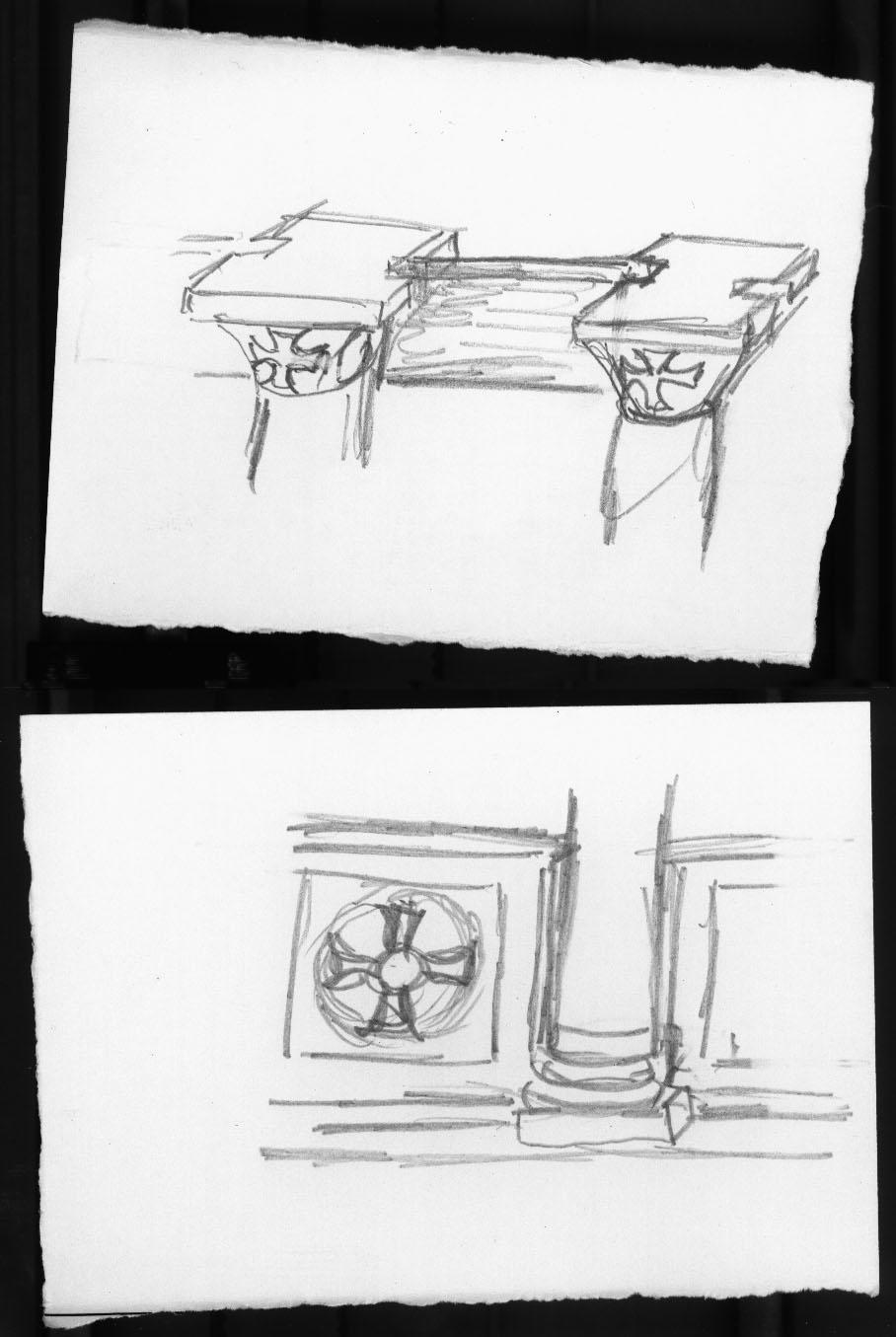

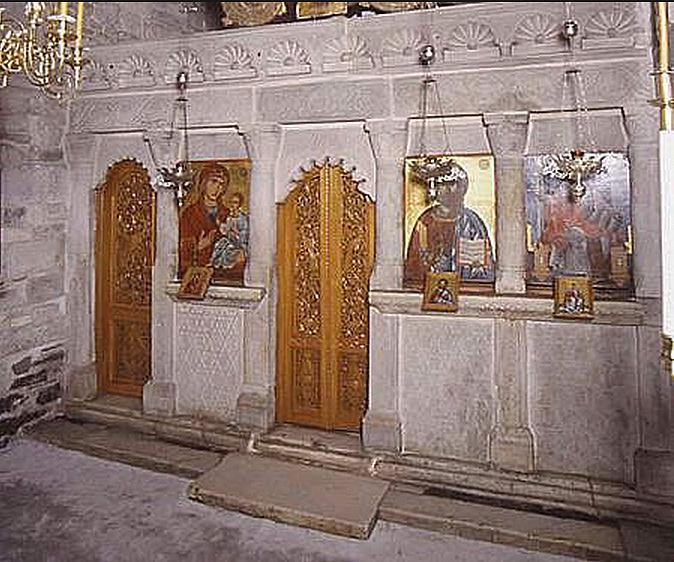

Nevertheless, if the exact spot cannot be determined, one element confirms the hypothesis of the ecclesiastical origin. On each lateral side of the capital and the base of the column, a cut is visible in which another element could be set. After comparison with other orthodox buildings, the same type of cut is found in the columns forming the templon and iconostases, architectural structures separating the bema (the area housing the altar) from the rest of the church.

The elements which were inserted were therefore slabs, of stone or marble, forming a balustrade at the base and an entablature at the top.

What can be said about the age of these vestiges ?

On the other hand, dating these archaeological pieces is less precise. Following the known evolution of these structures separating the bema (distantly recalling moreover the enclosures of the Western choir), an estimation can be made. We know that the first balustrades or columns were attested from the 4th century onwards, but they only separated at mid-height. It was not until the 6th-7th centuries for these structures to become monuments for the first time, at the level of the entrance door of the bema.

The total monumentalization of the structure and the appearance of entablatures developed between the 10th and 12th centuries (when they were called templons), and the last stage came in the 17th century with the installation of the icon between the base slabs and the entablature, completely hiding the altar from sight (the iconostasis).

©Michele Piccirillo

These ruins therefore come to us very probably from this third phase, that of the development of the templon. The church of St John the Evangelist was one of the oldest Georgian buildings in Jerusalem, attested from the early 8th century by the Armenian pilgrim Anastasius. However, the presence of indentations on the capital shows the presence of an entablature, dating these pieces to the 10th century at the earliest. As for the latest possible dating, it has to be remembered that the former Georgian convent was bought by the friars minor in the middle of the 16th century (in 1559 to be precise).

The period deemed most accurately by friar Alliata is that of the start of the templon, from between the 10th and the 12th century.

“The gestation of this museum was the occasion, for the Custody, to reclaim its heritage,” said Friar Stéphane Milovitch, director of the Cultural Heritage of the Custody of the Holy Land [1]. If this declaration referred to the campaigns of inventories carried out in the Franciscan shrines when the collection of the historical section of the Terra Sancta Museum was created, it does not make less sense in the context of the construction of its premises. The discovery of these medieval remains (which will be on display!) effectively offers a new opportunity to claim its heritage (this time, that of its place of residence) and above all its past. And the continuation of the structure work under the St Saviour church allows us to hope that the story is not yet finished…

(Translated from french by Joan Rundo)

[1] See our article : The museums of the Franciscans in Jerusalem. 120 years at the service of Christian history in the Holy Land