The Medici and Jerusalem

What link did the Medici family have with the Holy Land? And what prestigious gift did they give to the Holy Sepulcher? Franz Joseph Klos continues to explore the links between Tuscany and the Holy Land on the exhibition “The Treasures of the Holy Land at the Marino Marino Museum” which will open its doors on September 12, 2024.

It was during the “reign” of the Medici (fourteenth and fifteenth centuries) that the reproductions of the Edicule of the Holy Sepulcher were made in Fiesole and San Pancrazio (Cappella Rucellai in the Marino Marini Museum). Moreover, after the conspiracy of 1478 (in which several families attempted to overthrow the Medici’s power), the Medici took over the Scoppio del Carro ceremony (which was then a privilege of the Pazzi family) and began to establish important ties with the Holy Land. It was in this perspective that they set up a patronage with certain sanctuaries in the Holy Land and that they showed great generosity for the Holy Places.

A legendary episode even tells of their dream of moving the aedicule of the Holy Sepulcher to Florence under the dome of the Medici funerary chapel of San Lorenzo[1]! According to legend, the Grand Dukes Ferdinand I and Cosimo II tried through diplomatic channels to carry out this project in a context of expansion of Medici Eastern policy, a project that was also likened to a “crusade” against the Turks in connection with Emir Fakreddin (enemy of the Sublime Porte) from whom it was hoped that the abuses against minorities in the Holy Land would cease. This idealistic dream of the princes, far from being secondary, reveals their attachment to the Holy Land and the great devotion of the inhabitants of Tuscany to the holy places[2].

AN ALTAR FOR THE STONE OF UNCTION

But it is to Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549 – 1609, reigned from 1587 until his death, who was also protector of the Franciscan order when he was a cardinal) that we certainly owe the most prestigious gift to the Holy Sepulcher. It is also at the center of the attention of all pilgrims and has been for centuries since it is the altar in two parts installed on Calvary.

Every day Masses are celebrated there by the Franciscans, Custodians of the Holy Places, the priests of the universal Church in the company of pilgrims and the clergy of the diocese of Jerusalem and its faithful. It is also the place of the eighth station of the daily procession that the friars carry out within the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher. Finally, it is on this altar that the emotive Good Friday liturgy is celebrated every year, presided over by the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem.

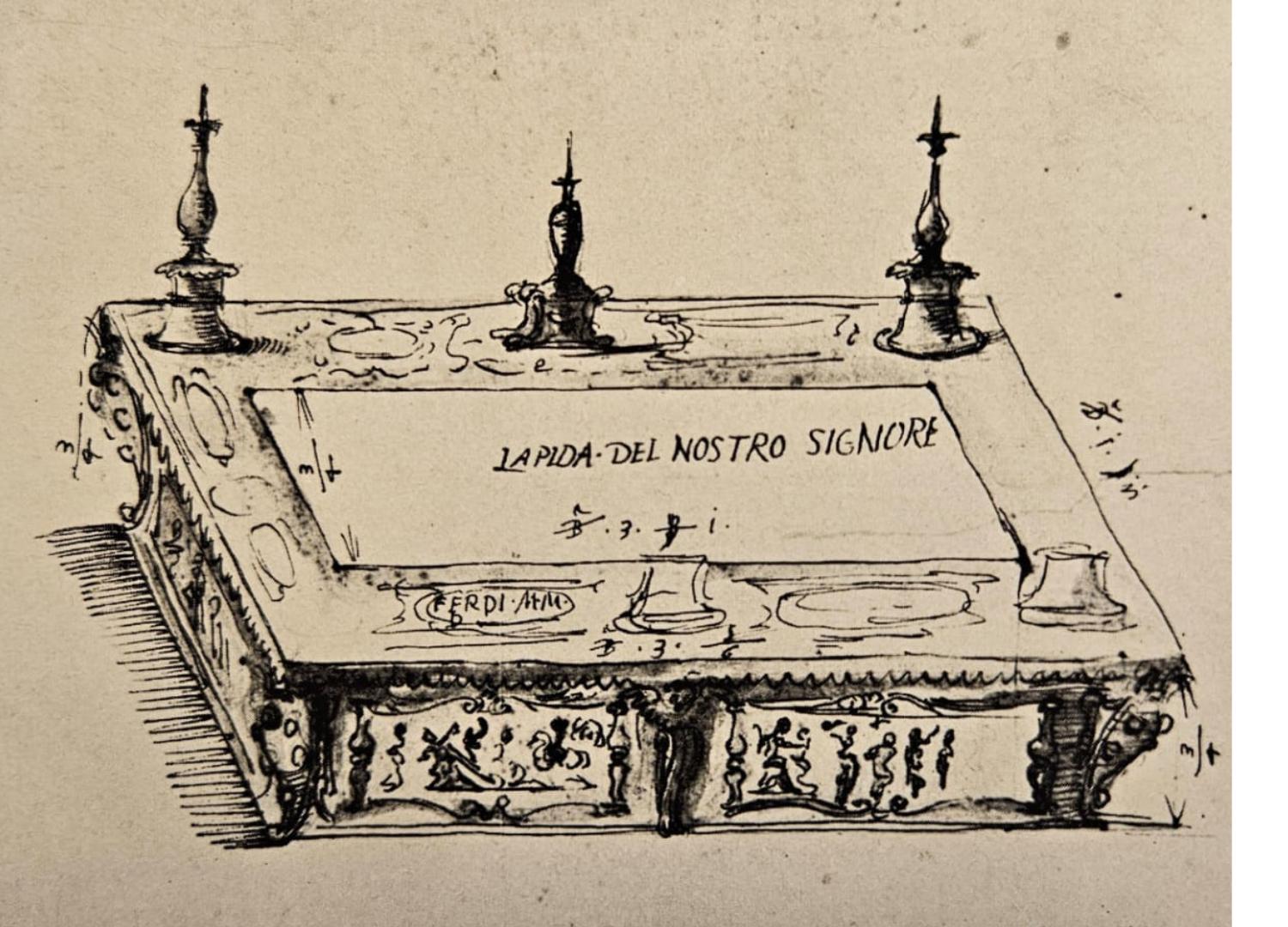

This altar is composed of two parts. The lower part, the most recent, was made by the brothers, helped by craftsmen and apprentices from the ironwork workshop of the Convent of St Saviour. This exceptional ironwork testifies to the integration of the friars into the local Christian community and their concern to train the younger generations in a craft of excellence. The upper part is a gift from the Medici. The story of this ornamento (we also find the Latin term arca) is not trivial. This massive gilded bronze work was made under the direction of Father Domenico Portigiani of the Convent of San Marco in Florence and contains six splendid bas-reliefs attributed to Pierre de Francqueville and his master, the sculptor John of Bologna. These six bas-reliefs each represent an episode of the passion and resurrection of Christ: The Elevation of the Cross, The Crucifixion, The Deposition from the Cross, The Anointing of Christ’s Body, The Burial and The Resurrection.

THE JOURNEY OF A WORK

This ornamento was made in Florence between 1587 and 1591 in the foundries of the Grand Duchy in St. Mark’s. Initially it was made to be a case for the Stone of Unction, and it is the six bas-reliefs that constitute the most splendid part of this bronze case. These masterpieces made by de Francqueville and Jean de Bologna are to be compared with other bas-reliefs made by these artists: those of the bronze doors of the cathedral of Pisa made at the same time.

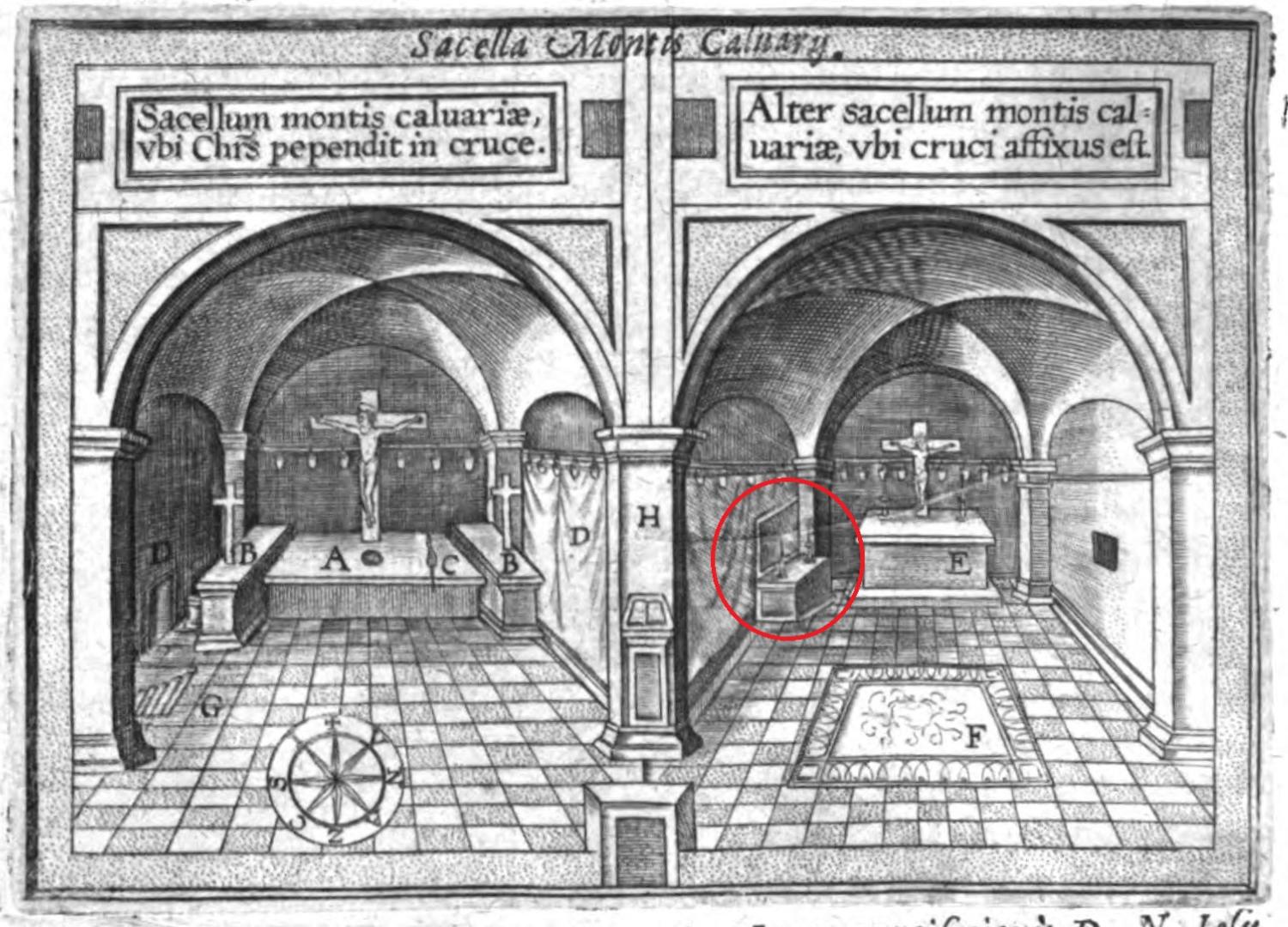

The arca was ready to be sent at the end of 1591 with other gifts from the Grand Duke for the Holy Sepulcher. The crates then stopped in Bologna and then Venice where they had to stay for three years before finally leaving on March 26, 1595, on board the galley Torniella. The boxes of gifts probably arrived in Jerusalem at the end of 1595, but the bronze case for the Stone of Unction turned out to be too small to hold it! Some friars even thought of asking the civil authorities in Jerusalem for permission to shorten the stone! Other testimonies suggest that the Greek Orthodox opposed and went to the judge and the governor of Jerusalem to explain that the presence of the crate would interfere with popular devotion to the sacred stone[3]. [TL1] The box was therefore never installed around this stone and the Franciscans placed it under the north arch of the Crucifixion Chapel where it was used as an altar.

In 1727, the bronze ornamento was transferred to the convent of St Saviour[4] and then in 1736 was again used as an altar, but this time in the chapel of Mary Magdalene before returning to the chapel of Calvary in 1856[5] (date on which the lower part in wrought iron was probably added), a position it still holds today.

AN EPIPHANY OF THE TERRA SANCTA MUSEUM

Fr. Stéphane Milovitch, director of Cultural Heritage of the Custody of the Holy Land, likes to say that this altar is “an epiphany of the Terra Sancta Museum because it is composed of two parts, one designed by the Church of Jerusalem and the other by the universal Church” (here represented by Florence). “This altar is in the image of our museum, which will house Palestinian works (collection of oriental icons, objects in olive wood and mother-of-pearl made in Bethlehem, etc.) as well as the Treasury of the Holy Sepulcher (chalices offered by Louis XIV, liturgical vestments of the Republic of Venice, gifts from Spanish kings…).

It is easy to understand why this Medici altar, which has been completely restored, is the centerpiece of the exhibition “The Treasures of the Holy Land” which will open on September 12 in Florence. We invite you all to come and admire this masterpiece that for the first time left the Holy City to be restored and then exhibited in its city of origin.

———————————————————-

Chronology of the Medici Altar

1587-1591: Realization of the work in Florence in the foundries of the Grand Duchy in Saint Mark[6]

16 November 1591: Ornamento ready to be sent[7]

22 May 1592: The object, which had recently arrived in Bologna, was sent to Venice[8]

30 May 1592: Arrival of the object in Venice[9]

The ornamento is in Venice, he stays there for legal and financial reasons[10]

March 26, 1595: Departure of the object aboard the ship Torniella for Jerusalem[11]

23 December 1595: Letter to Grand Duke Ferdinand I, informing that the dimensions of his gift do not fit with the Stone of Unction[12]

1595-1596(?): The Greeks protested to the Ottoman authorities, the box was installed under the north arch of the Crucifixion Chapel, it was probably used as an altar[13]

1727: Transfer to the St Saviour convent[14]

1736: Placed on the altar of Mary Magdalene[15]

1856: Installation of the altar in its current place on Calvary[16]

[1] Franco CARDINI: “La Toscana e la Custodia di Terra Santa” in Piccirillo, Michele (ed.), La Custodia di Terra Santa e l’Europa: I rapporti politici e l’attività culturale dei Francescani in Medio Oriente. Il Veltro, 1983.

[2] Idem

[3] Quaresmio, Francesco, and Sabino De Sandoli. Francisci Quaresmii Elucidatio Terrae Sanctae. Franciscan Print. Press, Jerusalem 1989. Page 271.

[4] KRIEGBAUM, FRITZ. “EIN BRONZEPALIOTTO VON GIOVANNI DA BOLOGNA IN JERUSALEM.” Jahrbuch Der Preuszischen Kunstsammlungen, vol. 48, 1927, pp. 43–52; Horn, Elzearius, and Girolamo Golubovich. Ichnographiæ Locorum et Monumentorum Veterum Terrae Sanctae. typis Sallustianis, 1902, pp. 243-245.

[5] Shannon N. Pritchard Giambologna’s Bronze Pictures: The Narrative Reliefs for Ferdinando I de’Medici and the Post-Tridentine Paragone, The University of Georgia July 2010

[6] Shannon N. Pritchard Giambologna’s Bronze Pictures: The Narrative Reliefs for Ferdinando I de’Medici and the Post-Tridentine Paragone, The University of Georgia July 2010

[7] Francqueville, Robert de. Pierre de Francqueville, sculptor of the Medici and King Henry IV (1548-1615). Editions A. and J. Picard et Cie, 1968.

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Quaresmio, Francesco, and Sabino De Sandoli. Francisci Quaresmii Elucidatio Terrae Sanctae. Franciscan Print. Press, Jerusalem 1989

[14] KRIEGBAUM, FRITZ. “EIN BRONZEPALIOTTO VON GIOVANNI DA BOLOGNA IN JERUSALEM.” Jahrbuch Der Preuszischen Kunstsammlungen, vol. 48, 1927, pp. 43–52; Horn, Elzearius, and Girolamo Golubovich. Ichnographiæ Locorum et Monumentorum Veterum Terrae Sanctae. typis Sallustianis, 1902, pp. 243-245.

[15] Ibidem and Francqueville

[16] Ibid