Modern Day Manuscript Illumination: “The Patience of an Angel and the Eyes of a Hawk”

Parisian Olivier Naude leads a double life. Insurance company researcher is his day job, but his true calling is manuscript illumination, and he has just completed several masterworks for the Terra Sancta Museum. Like the medieval artist monks of the Golden Age of Illumination, Naude is all precision, patience, and passion. Meet the man for whom the gold leaf holds no secrets.

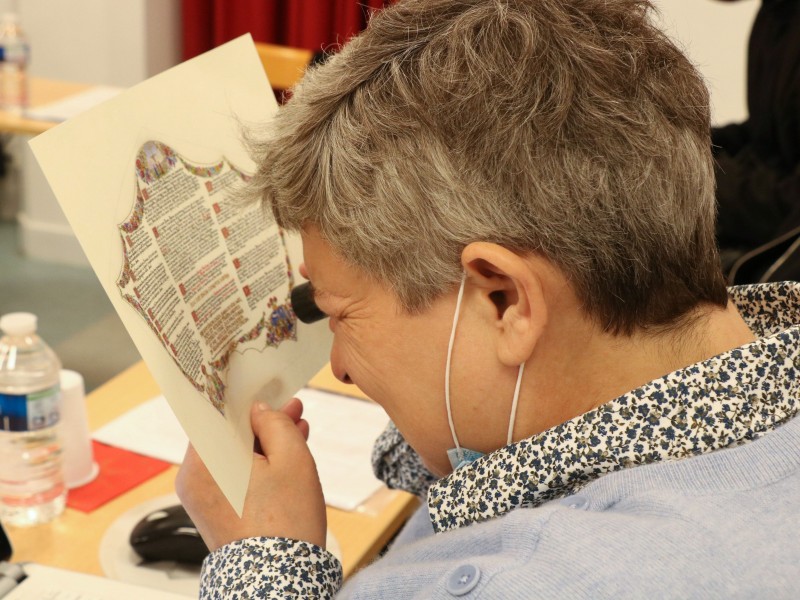

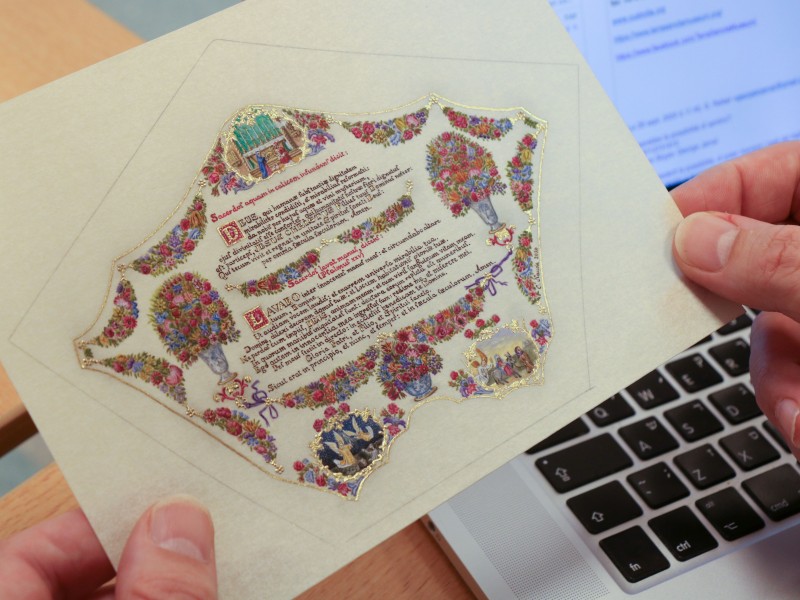

It’s the September 2020 meeting of the Scientific Committee of the Terra Sancta Museum, and Olivier Naude, who was invited to participate in a working session, carefully reveals the delicate sheets he has produced for the Museum. “What you see before you represent more than 400 hours of work” he humbly lets slip. Four-hundred hours to create three illuminated backdrops that will adorn mother-of-pearl altar canons from Bethlehem. The Committee members rave over the exquisitely painted motifs and calligraphy. A few days later, we find him in the cozy atmosphere of his Parisian apartment. Small paintings in shimmering colors dot the walls—many of which were recently shown in the 2019 exhibition “Illuminations: Painting Infinity in Miniature” at the Institution Sainte Marie Anthony, near Paris.

An Artist’s Versatility

An excellent teacher as well, Naude first explains that the art of manuscript illumination traditionally brought together several different trades: “…until the 18th century, masters of illumination worked with calligraphers and scribes who transcribed the text, and with gilders who added gold details to the manuscripts. These masters only take part in the decoration of the book. They were true artists. The greatest miniature painters of the late Middle Ages in France, Jean Fouquet and Jean Bourdichon, were first and foremost painters, as was their Italian contemporary, Fra Angelico“. Today, however, he explains, manuscript illuminators no longer work in a “workshop” or together with other artisans. Therefore they must also carry out the calligraphy and gilding themselves before finally getting to the painting, the heart of their profession.

Naude works on special papers that mimic parchment and real parchment—lamb or kidskin that takes weeks to prepare. The first stage of the work is the “ruling” or layout—setting down the lines that will guide the letters’ writing. Then the calligraphy is added. Next is the preliminary drawing, and then the gilding, a step that requires great attention to detail. “It may seem surprising, but the gilded parts are done just after the drawing. Gold leaf cannot be applied after painting, because the metal flakes which are dusted off [during the gilding process] tend to adhere to [wet] paint…”, explains this enthusiast.

But what made the manuscripts of the 5th to 18th centuries famous was the breakthrough use of color—from natural pigments—giving depth and glow to the miniature paintings of the manuscripts. Works so famous that even the French revolutionaries would not dare to destroy them during the numerous looting of abbey libraries, says Olivier. “We must not forget that, up until the Renaissance, the two great supporter-protectors of painting were the walls of churches and the book. As books are kept closed, the paintings in them have been perfectly preserved, and are [still] dazzling to the eye!”. This art form and cultural heritage are becoming more widely known now that many manuscripts have been digitized and made available online.

Inspiration and Creation

Scientific Committee member Jacques Charles-Gaffiot contacted Olivier Naude during the restoration of the 17th and 18th-century altar canons produced by master mother-of-pearl workers from Bethlehem. Naude noted that the text on these “Mass cards for the celebrant” had all but disappeared. “I first had to transcribe the liturgical texts, which are obligatory and consecrated by centuries of use, but in the smallest size possible, to leave a little room for the painting because I am first and foremost a painter, not a calligrapher!”. Quite a challenge for an artist who usually works on formats ranging from ten to twenty centimeters: “I didn’t think I could make calligraphic characters so small. I pity the poor celebrant who will have to use it. He is going to tear his eyes out!” he joked.

Naude was then able to unleash his imagination for the miniature paintings. “For the first cannons, I was inspired by the manuscripts commissioned by Louis XIV from the illuminations workshop at Les Invalides, in Paris. They were most suited to the frame. For the second commission…the barrels are a little larger and recall the Italian Baroque, so the 15th-century Florentine manuscript inspired me, the Breviary of King Matthias Corvin of Hungary, a very richly decorated work”.

Illumination, an Expressive Art Olivier Naude, seated in front of his drawing board, juggles between brushes and materials with ease to show us the gilding and color he is endeavoring to apply. The garlands on the central barrel are made up of more than 260 flowers and little buds; as for the medallions, they faithfully retrace the childhood of Christ to the place of production of the frame—Bethlehem. “My job is to render the infinitely small, but also never to forget that it is an expressive painting, despite its size—not the footprints of flies! Doing so is not a mystery—a successful painting comes from a successful drawing, that is to say, finely drawn and expressive lines. A bit like how their character traits can define people!”.

Progress is slow, and the work painstakingly delicate to preserve what has already been achieved. “Look at these backgrounds, only a succession of tiny brushstrokes allows you to achieve this velvety gradient of blue; see how the Virgin’s coat—which is itself blue—stands out from the background”, indicating the area on the first canon, which will return to Jerusalem very soon. The artist concludes with a touch of humor: “The most difficult part of manuscript illumination is perseverance! You need to have the patience of an angel and the eyes of a hawk! It is a contemplative profession; I can see why there are monks, totally unknown, who have practiced this art during the centuries, chanting their psalms between illuminating sessions “.