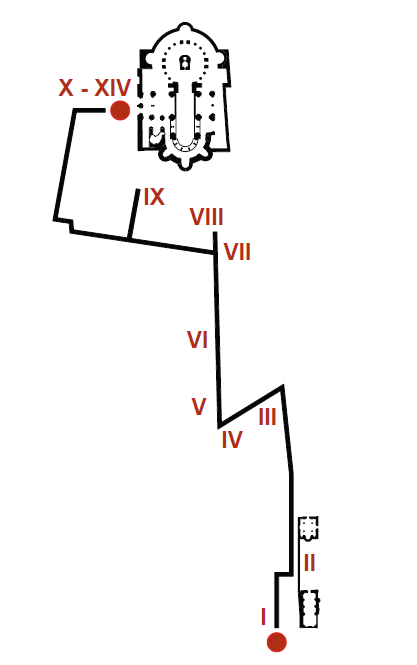

The fourteen stations of the Via Dolorosa

I. Jesus is condemned to death

On the right side of the street leading to Lions’ Gate, a slope goes up toward the el-Omariyyah school; its courtyard serves as the starting point for the Way of the Cross. In the 16th century, the site commemorating Jesus’ condemnation was transferred from the nearby Church of the Flagellation to the governor’s palace (the Turkish capigi-bashi). It was only logical that the Western pilgrims would end up associating the town governor’s court with the place where Pilate condemned Jesus. This is also the palace of the Herodian Antonia Tower.

Most of the buildings in this complex date back to the 14th century (Madrasa al-Jawiliyya) or to the first half of the 19th century. They were used as a barracks for a long time, before being rebuilt as an elementary school by the British in 1927. An enclosed building found in the southern wing, has been identified as the medieval “Chapel of Rest,” or “Chapel of the Crowning with Thorns.” However, all that remains of the building, which was badly damaged during an earthquake in July 1927, is a section of the wall and portions of the arcades. Sculpted capitals from the Crusader area are preserved in the Islamic Museum. From the terrace the pilgrim has a good view of the Haram al-Sharif.

Situated opposite the Arab school, the convent of the Flagellation is the centre for a Scriptural and theological faculty, the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, to which we owe important discoveries concerning the origins of the Church and the Holy Places.

The ground floor of the convent is also the site of the Studium’s museum of archaeology, as well as the new multimedia section of the Terra Sancta Museum – Via Dolorosa.

The Church of the Flagellation (known locally as Habs al-Masih, or “The Prison of Christ”) was built in the 12th century, and since then has undergone several adaptations. Pilgrims’ reports have described it being used as a refuse dump, a stable, and a weaver’s shop. The place was a little more than a mound of ruins, when in 1838 it was granted to the Franciscans by the Egyptian Ibrahim Pasha, conqueror of Jerusalem. Hastily rebuilt in the following year thanks to the generosity of Maximilian of Bavaria, the church was entirely restored in 1927-29 by architect A. Barluzzi. The three magnificent stained glass windows in the choir are the work of L. Picchiarini after the design of D. Cambellotti; they represent the Scourging, the Washing of Hands and the Triumph of Barabbas (Matthew 27:24-26).

II. Jesus receives the Cross

The second chapel enclosed by the wall of the Franciscan convent commemorates both the Condemnation and the Imposition of the Cross. The chapel was built in 1903-1904 by a Franciscan monk, Br. Wendelin of Menden over earlier remains. Placed on its outside wall is the number of the second station, which before 1914 was located in front of the walled-up Mamluk gate, about 60 yards to the east. The wooden and papier-mâché statues in the chapel show Jesus during the first scenes of his Passion. On the south wall is a representation of St. John, trying to hide from the Blessed Virgin Mary the sight of Jesus carrying his cross.

The floor of the chapel is made of large paving stones, some of which show grooves and games cut into the stone, just as on many Roman pavements. This pavement extends to the north of the building, as far as the museum area and the neighbouring convent of the Sisters of Sion. It is generally the Lithostrotos (John 19:13) but more likely belonged to the Aelia Capitolina of Emperor Hadrian (2nd cent. AD).

The Roman arch that spans the Via Dolorosa is one of the best known in Jerusalem, due to the role that tradition has assigned to it in the story of Jesus’ Passion. The best-preserved of its three arcades are the central one, which spans the greater part of the Via Dolorosa, and the northern one, the remainder of which can be seen in the Ecce Homo basilica. The remains of the southern arcade have been incorporated into a private building. The modern set-up of a loggia with two windows has helped guides to envision the spot where Pilate presented Jesus to the crowd, thus leading to the name Ecce Homo, Latin for “here is the man” (John 19:5), which it has kept until today.

The grounds of the Convent of the Sisters of Sion stretch on the right side of the Via Dolorosa, from the Convent of the Flagellation to the Greek Orthodox “Praetorium”. The convent, built in 1857-1868 by a Jewish convert, Fr. Marie-Alphonse Ratisbonne, encloses the new Ecce Homo basilica, most of the pavement called Lithostrotos and a great underground reservoir identified by archaeologists as being the Struthion mentioned by Flavius, Josephus in his account of the siege of Jerusalem (The Jewish War, V, 457).

The Greek Orthodox possess a part of the counterscarp of the Antonia, a section of the old street paving, and one grotto in particular which they show as the Prison of Christ. An old greek tradition favoured the north side of the street as the residences of the High-Priests, Annas and Caiaphas (John 18:12). The House of Herod Antipas (Luke 23:6-12) is also a place found nearby, together with a putative Prison of Peter the Apostle.

III. Jesus falls the first time

Beyond the Greek Praetorium the Sorrowful Way descends towards the Valley of Tyropoeon. At the Valley crossroads the Sorrowful Way turns left, and for about 40 yards follows the street which comes down from Damascus Gate. Ever since Ricoldus de Monte-Crucis (1288), pilgrims link the junction of the two streets to a fall of Jesus and the requisitioning of the Cyrenian. Today the spot recalls the episode of the first fall.

To the left, on the entrance of the former Turkish baths (Hammam as-Sultan), a chapel was built in the second half of the 19th century and renovated in 1947-48, thanks to the generosity of Polish soldiers quartered in Jerusalem. In front is an iron railing, its pillars are made from two pieces of a column which before was laid on the ground, and marked the actual spot of the station.

IV. Jesus meets Mary his mother

A bas-relief sculpture by T. Zielinski, representing the meeting of Jesus and Mary, rests above the door that leads into the church for the third and fourth stations. During the construction of the current church, which is owned by the Armenian Catholics, ruins were found of a building dating to the 13th century. On the site of the southern apse, the excavators brought to light a fragment of a fairly delicate mosaic, dated from 5th-6th cent., decorated with a design of two black sandals. This chapel appears to coincide with the church of Our Lady of the Fainting (Sancta Maria de Pasmason), mentioned by the mediaeval pilgrims. Some have quite naturally concluded that the sandals in the mosaic mark the spot from where the Blessed Virgin witnessed her son carrying the Cross. The present chapel serves as crypt to the church of the Armenian Catholics.

Until a few years ago, the fourth station was commemorated a few yards further down on the Via Dolorosa, near the opening of an alleyway.

V. Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus to carry the Cross

Before turning in the direction of Calvary, the pilgrim sees before him on the left a house that bridges el-Wad Road. Since the 14th century, tradition has held the building to be the house of the Rich Man who refused to help the beggar Lazarus (Luke 16:14-31). Just at the bend of the Via Dolorosa, we find the location, dating from the 15th-16th cent., of another house, of Simon the Pharisee, where a sinful woman anointed the feet of Jesus (Luke 7:36-50).

About 1850, the place was chosen to commemorate the requisitioning of Simon the Cyrenian, who was compelled to bear the cross of Jesus (Mark 15:21), and in his memory the Franciscans have set up a small oratory.

VI. A woman wipes the face of Jesus

A succession of flying buttresses makes the sixth station of the Via Dolorosa one of the most picturesque sites in Jerusalem, where tradition since the 15th century has placed the house of Veronica (an approximate Latin spelling of the Greek name Berenikes). The sixth station is shown on the left by a piece of pillar embedded in the wall of a house which bridges the street.

The site, which was bought at the end of the last century by the Greek Catholics, comprises an upper church and a crypt. It has ancient remains which could have been water reservoirs during the last centuries, and which can be linked to a Byzantine oratory said of Saints Cosmas and Damian. The “house of Veronica” is today that of the Little Sisters of Jesus, a religious congregation inspired by the life of Blessed Charles De Foucauld.

VII. Jesus falls the second time

The Via Dolorosa continues to rise and it rejoins the suk of Khan ez-Zeit (“the market for oil”). This crossroads is also the meeting-point of the cardo maximus (the main street) and one of the decumani (transverse roads) of Hadrian’s Aelia Capitolina. Since the end of the 13th century, pilgrims have held this spot to be the gate where authorities used to announce and publish court sentences, and through which passed the road to Calvary; hence its name, “the Judgment Gate” (Porta Iudiciaria).

Today the place is associated with the second fall of Jesus, according to Burchard of Mount-Sion (1283). The Franciscans have owned the site since 1875, and in 1895 they built two coinciding chapels where a large pillar of reddish stone is kept, part of the remains of Aelia Capitolina.

VIII. Jesus speaks to the Daughters of Jerusalem

After crossing the suk, the Via Dolorosa continues upwards for about 20 yards. Along its left side is the German hospice of Saint John, decorated with a Maltese cross, as well as the Greek convent of Saint Caralambos. A stone embedded in the wall of this latter building has a Latin cross and the words in Greek, “Jesus Christ conquers,” which marks the Gospel incident of the Daughters of Jerusalem who bewailed and lamented Jesus’ fate (Luke 23:28).

This episode has been memorialized in different places throughout the centuries, and it was only in the middle of the 19th century that the Franciscans moved its commemoration to its current location beyond the Judgment Gate.

IX. Jesus falls the third time

The pilgrim retraces his steps as far as the crossroads of the seventh station, and turns right into the suk. The roundabout direction is due to the construction of different buildings added later, after the death of Jesus. Shortly, another right turn is necessary, up the wide stairway and the winding road leading to the ninth station. The shaft of a pillar encased in the wall of the Coptic Patriarchate here marks the third fall of Jesus.

The third fall that Jesus suffered as he neared Calvary was originally commemorated within the courtyard of the Holy Sepulchre, and marked by a stone with a cross engraved upon it.

On the left is the shelter of the Ethiopian monks, which sits on the remains of the Constantinian basilica (Martyrium). From there a narrow passage leads directly to the plaza in front of the church of the Holy Sepulchre. Otherwise the pilgrim must retrace his/her steps to the street in the bazaar.

X. Jesus is stripped of his garments

The church of the Holy Sepulchre contains the last five stations of the Way of the Cross and includes Calvary and the tomb of Jesus. Having entered the church, the pilgrim goes at once to the right and up one of the two stairways to Calvary. A great part of the platform of Calvary rests on an infrastructure; only the eastern part of the nave on the left is built directly onto the rock.

The tenth station is located at the beginning of the nave, on the right. The inclusion in the Way of the Cross of the stripping of Jesus’ garments (Matthew 27:35) only appeared in Jerusalem at a later period.

XI. Jesus is crucified

A space of only a few yards separates the tenth and the eleventh stations. The pilgrim stands here in the Latin nave restored by A. Barluzzi in 1937. The mosaics on the ceiling are the work of P. D’Achiardi, who preserved a mediaeval figure of Christ. The altar of silvered bronze was a gift of Ferdinand I de Medici. It is purported to be the work of the Dominican artist Domenico Portigiani (1588), and was originally intended for the stone of Anointing. Its panels represent scenes from the Passion.

On the right, a window protected by a grill opens onto the chapel of the Franks, dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows and Saint John. Tradition makes it the place to which Mary withdrew during the preparations for the Crucifixion.

XII. Jesus dies on the Cross

Tradition places the erection of the cross and the death of Jesus in the eastern part of the nave on the left. A silver disk with a central hole, underneath the Greek Orthodox altar, marks the spot where the cross would have stood. During the time of Constantine this station was marked with a wooden cross; in 417 the emperor Theodosius II replaced it with another cross made of gold and precious stones.

To the right of the altar under the glass surface is seen the cleft that an old tradition links to the earthquake mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew (27:51).

XIII. The body of Jesus is taken down from the Cross

The Latin altar of the thirteenth station is placed between the two preceding stations, and is decorated with a wooden bust of Our Lady of Sorrows offered by Portugal in 1778. In Jerusalem the deposition was usually linked with the anointing of Jesus, which is commemorated to the west of Calvary at the stone of the Anointing. Before the crusades, this was the location of the Chapel of Saint Mary, but has been venerated as the place of Jesus’ anointing ever since the 13th century. The stone covers the rock on which Jesus’ body would have been laid (Matthew 27:57-60).

Ancient pilgrims would have seen a black, green, or white stone memorialising Jesus’ anointing; today it is covered with a red, polished block with a Greek inscription written around it: “The noble Joseph, taking the sinless body down from the wood, came with a clean linen shroud and aromatic spices and buried it in an empty tomb.”

XIV. The body of Jesus is placed in the tomb

In order to reach the Sepulchre, the pilgrim descends from Calvary, passing by the stone of the Anointing and near to a circular slab surmounted by an iron cage: from this latter spot the holy women would have looked from afar at Jesus on the cross (Matthew 27:55).

The Sepulchre stands in the middle of the Rotunda, known by the Greek name Anastatasis (Resurrection). It comprises the chapel of the Angel and the funeral-chamber itself. As it stands today it is a Greek restoration dating from 1810. The chapel of the Angel replaces the original antechamber of the tomb. According to tradition, the marble pedestal standing in the middle is said to contain a fragment of the circular rock that was used as a door to the tomb.

A small arched opening leads from the chapel to the funeral chamber. Since the destruction by al-Hakim in 1009, only the lower parts of the chamber subsist. The remainder is hidden by a marble facing. A marble slab, marked by a crack all the way across, was placed over the northern bench in 1555 by the Franciscan Boniface of Ragusa, Guardian of Mount-Sion.

The empty tomb of Jesus remains as witness to his glorious resurrection (Matthew 28:6).

- This is a revised summary of a chapter from the valuable book by A. Storme, “The Way of the Cross”, Jerusalem 1984.