From the Middle Ages to contemporaneity: the representation of the encounter between san Francis and the sultan in art

During the celebrations for the anniversary of the 800 years since the encounter between san Francis and the sultan al-Malik, the book by Rosa Giorgi “Francis and the Sultan in art”, recently edited by Edizioni Terra Santa, has been presented. The author, an Italian art historian and head of the Museum of the Capuchins in Milan, reviewed the iconographic history of this renowned encounter from the Middle Ages to contemporaneity.

The volume is introduced by fra Cesare Vaiani’s paper: it precisely describes inside and external sources to the Franciscan order which have handed down the event over time. From the sources it can be deduced that the encounter took really place in 1219, even though the content of the dialogue between Francis and the sultan remains unknown. “All we know is that the outcome (of the conversation) was, despite the expectations of the contemporaries and, perhaps, of Francis himself, peaceful and marked by the sultan’s courtesy”, writes Vaiani.

“The figuration is a testimony of the way in which the event has been acknowledged”, stated Dr. Giorgi at the opening of her presentation, to explain that the representations of this episode represent the time in which they have been realized, rather than the event itself.

Therefore, in the first existing representation of the subject – in the Pala Bardi (Florence, Basilica di Santa Croce, chapel Bardi, around 1243) – the sultan becomes a Byzantine sovereign. He is probably the only example of an Oriental monarch known by the altarpiece’s artist, namely Coppo di Marcovaldo. The representation is based on the only source that the artist had available at that time: Vita Prima by Thomas of Celano. The latter focuses on the efficacy of the preaching which takes place in front of a large group of Muslims, and not much on the violence suffered by Francis before reaching the sultan. This, despite being handed down by Thomas of Celano, has not been depicted.

The pacific tone of the dialogue will be abandoned in a few years, due to the preference for the official biography of Francis as a source, written by san Bonaventura. He narrates the episode of “the fire proof”, where Francis defied the sultan’s ministers. However, according to Bonaventura, the flame was never lit, because the proof was denied by the sultan; and yet Giotto (in the Basilica Superiore of Assisi) and many other artists after him, represent this moment, transforming Francis’ testimony from preaching to challenge with the Muslims.

There are representations where the emphasis is placed on the strength of Francis’ preaching:

In the Antiphonary of Budapest (around 1450), the artist depicts, again, the fire proof, shifting the emphasis from the fire – which is relegated to the background – to Francis’ gesture of illustrating the Gospel to the Muslims. In fact, the saint is depicted while counting on his fingers, a gesture that in the Middle Ages was associated with those who taught with authority. On the back of Francis, brother Illuminato, with joined hands tucked in the long sleeves of his robe, holds an object identifiable as a book kept in a case: this is probably the Gospel, containing the written Word of Christ, Incarnate Word, in support and proof of what Francis announces.

[it]Coppo di Marcovaldo, Francesco predica davanti al Sultano, 1243 ca, Firenze, Basilica di Santa Croce, Cappella Bardi[/it][en]Coppo di Marcovaldo, Francis preaches before the Sultan, c. 1243, Florence, Basilica of Santa Croce, Bardi Chapel[/en][fr]Coppo di Marcovaldo, François prêche devant le Sultan, vers 1243, Florence, Basilique de Santa Croce, Chapelle Bardi[/fr][es]Coppo di Marcovaldo, Francisco predica ante el sultán, c. 1243, Florencia, Basílica de la Santa Cruz, Capilla de Bardi[/es]

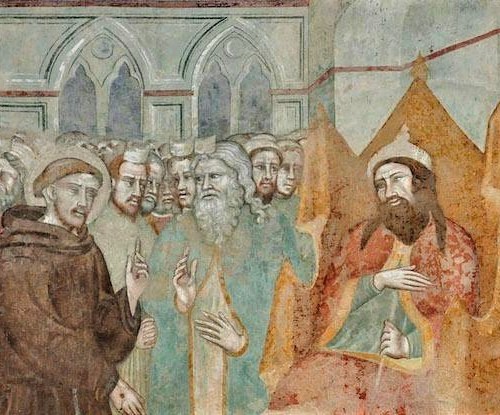

[it]Giotto di Bondone, Francesco e la prova del fuoco, 1289 – 1292, Assisi, Basilica superiore di San Francesco[/it][en]Giotto di Bondone, Francis and the Proof of Fire, 1289 – 1292, Assisi, Upper Basilica of St. Francis[/en][fr]Giotto di Bondone, François et l’épreuve du feu, 1289 – 1292, Assise, Basilique supérieure de Saint-François[/fr][es]Giotto di Bondone, Francesco y la prueba de fuego,1289 – 1292, Asís, Basílica Superior de San Francisco[/es]

In medieval representations, the hostility of the Muslim population becomes rather pronounced. For instance, in Pienza, in 1380, Cristoforo di Bindoccio represents in his cycle of stories about the saint in the Church of Saint Francis the sultan and his entourage as a group of Jews. They were considered as infidels as the Muslims, but much more well-known and poorly tolerated in 14th century Tuscany. In Spain, in the lower register’s frame of a large altarpiece dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the author – Nicolás Francés – reveals the Muslim’s hostility, closure and conflict. In fact, he represents the sultan as a fierce sovereign with a thick black beard, focusing on the mistreatment of Francis and Illuminato. It is clear that the interpretation of the episode in mid-14th century Spain is linked to the fear of the Muslim enemy, with whom the Spanish were fighting in those years in the Iberian Peninsula.

During the Renaissance, in some cases, the scene assumes the characteristic of a theological dispute: for example, in the chapel Sassetti in Santa Trinita in Florence, painted by Ghirlandaio. By contrast, after the Council of Trent (1545), during the period named by Rosa Giorgi as “the time of the Great Silence”, the episode acquires moralizing meanings (even to the extent of depicting the sultan’s conversion, which no source mentions). In other cases, it borrows the iconography of martyrdom, which is typically Tridentine; an example is Pomarancio’s fresco (namely Nicolò Circignani) in the church of san Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome.

According to Rosa Giorgi, at the end of the 18th century, with regard to the representation of the episode in this time period, “occurs the transition from the fear of the foreign to a new look towards the East: the scene will be depicted without threatening figures, affronts and challenges like the fire proof”. In fact, 19th and 20th-century artists, fascinated by the East and history painting, were more interested in making the episode realistic, focusing on landscapes, costumes and settings, rather than on the hostilities. Emblematic of this is Paolo Gaidano’s painting, 1898, housed in the convent of St Savior in Jerusalem.

The path ends with contemporary representations of the episode, which, in many cases, represent the desire for a real dialogue. An instance is 2009 Marko Ivan Rupnik’s mosaic representing the encounter between Francis and the sultan in the sanctuary of san Giovanni Rotondo in Foggia. Francis and the sultan are depicted while sitting on the same carpet: Francis is explaining the Holy Scriptures to the sultan, who listens to him with open arms. On the edge of the carped one can see food, a sign of a shared meal. Frère Stéphane Martin-Prével, depicts Francis and the sultan while hugging each other: this is a reinterpretation of the episode which focuses on aspirations for peace and fraternity, a common aim of the entire humanity. As the author writes, Francis and the sultan hug each other, and “conscious of what divides them, let their hearts speak and then recognize themselves as brothers”. What is in the hearts of the two that enables them to recognize themselves as brothers? The presence of God, written in Arabic letters in the sultan’s heart and depicted as embodied in Christ in Francis’ heart.