Painting for the Holy Land : Giacomo Martinetti and The pilgrims of Emmaus

A native of Switzerland but naturalized Italian, Giacomo Martinetti was born in 1842 in Barbengo, in the Ticino canton in southern Switzerland. The descendant of a wealthy family which had made its fortune in Algeria, he was sent as an adolescent to Florence to study with the painter Antonio Ciseri. From his master he learned the art of painting, which he made his career, but also and above all a naturalist style with almost photographic effects.

On the occasion of the publication of a catalogue for the two hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth by the Pinacoteca Cantonale Giovanni Züst, here is a look back at one of the masterpieces by this artist, which was given to the Custody of the Holy Land for the church of St Cleopas in Emmaus (Al-Qubiebeh).

“And it happened that, while he was with them at table, he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them. With that their eyes were opened and they recognized him, but he vanished from their sight.” (Luke, 24:30-31).

Described in Chapter 24 of the book of Luke, the scene known as the “Pilgrims of Emmaus” is one of the most important episodes witnessing the Resurrection of Christ in Christian history. With this title, many artists have taken on this subject over the centuries and so it was natural that one of the places today potentially identified as the Biblical Emmaus [1] should receive a painting of it. It was under the impulse of Friar Remigio Buselli [2] in 1890 that the artist Giacomo Martinetti was asked to paint a picture for the Franciscan shrine of Emmaus, located in the present-day town of Al-Qubeibeh in Palestine.

At first sight, the aspect which no doubt is the most impressive in this painting is his concern to faithfully transcribe reality. In the continuity of the art of Antonio Ciseri, Martinetti’s painting is effectively characterized by a very naturalistic rendering of the scenes which is found both in the rendering of the textures (in particular of fabrics) and in his work on lighting or volumes

© Gali Tibbon Studio / TSM

This quest for fidelity to nature, characteristics of the academic trends of the second half of the 19th century, is not without recalling photography which, it must not be forgotten, was invented in the same century. Lingering over the characters, we can also notice some micro-details such as the creases in the tablecloth caused by the movement of the body of St Cleopas (on the left), the bulging tendons in his right arm (the sign of a muscular contraction) or also the fact that Simeon is gripping his stool (on the right).

Although subtle, these details elegantly show a desire to give an effect of capturing the instant of the scene which, while it greatly uses the subject described (we will return to this), also tries to show (and defend) the expressive potential of the art of painting. It is effectively well known today that the development of photography in the 19th century brought about a questioning of the legitimacy of painting as an art of representation. Far from condemning it, however, this event favoured the development of new ways of painting, at times trying to rival photography on the level of realism.

The analysis of this painting would however be incomplete if we did not look at another source of inspiration of the style of Ciseri and de facto of Martinetti. Antonio Ciseri studied under Tommaso Minardi, the cofounder of Italian Purism, a movement advocating a return to religious subjects as well as a re-assessment of the art of the Italian 14th and 15th centuries. Consequently, it is interesting to consider the contribution of the Italian academic tradition to this painting of the pilgrims of Emmaus.

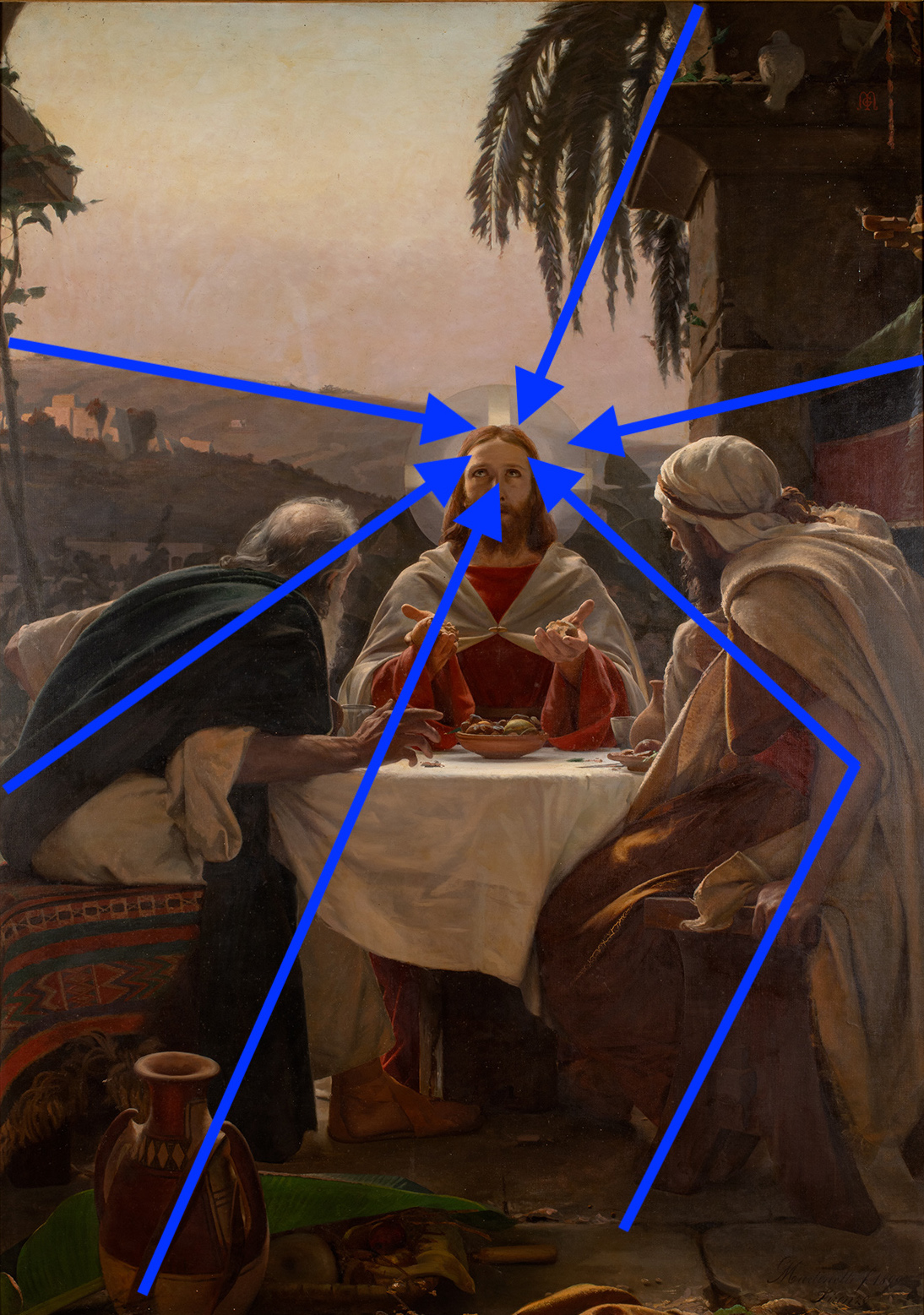

A first point of analysis could concentrate on the balance and stability that emerge from the scene. They are the result of a triangular construction inherited from the Florentine 15th century, which can be observed in particular in the spatial distribution of the three characters or even more through the body of Christ Himself. Another element reinforces this effect: the distribution of the colours and of certain elements in the shape of an “X”. If we look carefully at how the painting is constructed, we can notice for example that the emptiness of the sky at the top-left reflects the emptiness of the foreground below right, and inversely, that the “fullness” produced by the elements on the ground below-left recalls that produced by the architecture at the top-right. In the same way, the light colour of the sky answers Simeon’s robe which is diametrically opposite and the dark shade of the stone of the wall finds its correspondence in Cleopas’ drape. This layout of construction allows giving each side of the painting an equivalent element in order to avoid any imbalances.

How can we read the painting? At the beginning of our analysis, we approached the naturalist side of the representation, but without raising the question of depth and then of perspective. In painting there are three types of perspective, the best known and most widely used one of which is called “linear” [3]. Theorized in the 15th century as well, it subjugates the construction of the painting to Euclidian geometry and orients the profile of the elements making it up towards a vanishing point. Without going any further into the details of this technique, it was important to mention it, on the one hand because the work we are concerned with builds its depth through this perspective, but on the other hand – through the vanishing points – it has led to the birth of what are called “key elements”.

These, which are not necessarily dependent on the vanishing point, aim to guide the gaze to help it in reading the scene.

Where do we find this type of line in this painting?

If the vanishing points can be easily identified (the paving of the ground and the profile of the architecture of the right, in particular), the key elements are more subtle, even though they are responsible to a great extent for accompanying the gaze. As Jesus is the most important element in the scene, it is completely natural that everything tends to orient our gaze towards Him. We can then notice the lines formed by the back and then the head of Cleopas, by the arm and then the shoulder of Simeon, by the leaves above Christ or the horizon of the landscape in the background and even the diagonal strap which is attached to the piece of pottery in the foreground. All these, plus the vanishing lines, allow us, wherever we look in the composition, to return to its central element, Christ, who at the precise moment of the painting has just been recognized by the two disciples.

In order to conclude this point, we can add two last stratagems that also allow leading our gaze to the figure of Jesus : the schematic treatment of the landscape which contrasts with the naturalism of the scene and acts as a repoussoir on the latter ; the postures of the two disciples which, combined, make us gradually enter the composition and thus towards Jesus (Simeon, from the side, includes us in the scene and Cleopas directs us towards Christ).

Lastly, a final word must be said concerning the iconography of this painting. The moment chosen by Martinetti is the one which concludes this moment of the gospel according to Luke : Jesus, after having walked with the two disciples from Jerusalem to Emmaus, explaining the Scriptures to them once again [4], sits down at a table with them and, as he breaks the bread, disappears at the very moment they recognize him. We have to understand that the scene shown only lasts a fraction of a second. This explains first of all the need for an effect of instantaneity that we mentioned earlier in this article, but also, to express this moment of disappearance as it is about to take place, the artist shows Jesus looking upwards. This allows two things to be shown: concretely, he is mentally no longer with the disciples and, symbolically, he is showing his next destination, heaven.

The colours worn by Christ are also not inconsequential. Red, the colour of blood, symbolizes his condition as a martyr. However, over the red garment he wears a white robe, the colour of purity and of Glory which refers to the Resurrection shown in this scene: red covered by white symbolizes that death has been defeated.[5]

Initially in the chapel of the Seraphic Seminary of Al-Qubeibeh, the painting by Martinetti of the Pilgrims of Emmaus was moved to the Basilica of St Cleopas, built opposite in the first decade of the 20th century. The scene that the artist chose to show this important passage of the gospel according to Luke is very classic, easily justified by the educational function that it also had to have on the faithful. For all that, the analysis of this painting allows us to fully appreciate the richness of its conception which shows both the complexity of academic art and the survival of the latter in a period when the trends of the avant-garde, more and more numerous, were flourishing on the European artistic scene.

(Translated from french by Joan Rundo)

Terra Sancta Museum warmly thanks Gali Tibbon for the photograph of this painting.

Gali Tibbon Studio : FB, INS

[1] To date, six places have been proposed as corresponding to the Biblical Emmaus, three of which are considered the most probable : Emmaus Nikopolis, Al-Qubeibeh and Abu Ghosh.

[2] A Franciscan who at the time was the Commissar of the Holy Land. In particular he wrote several studies on the localization of the Biblical Emmaus in the 1880s.

[3] There also exists atmospheric (or aerial) perspective, reproducing the effect of distance by the gradual fading of the colours in the background and the “three-point” perspective consisting, again in the background, of having areas coloured ochre-brown followed by green and lastly blue (the progressive passage from a warm colour to a cool colour accentuating the impression of distance).

[4] “Then, beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them what referred to him in all the scriptures.” (Luke, 24:27).

[5] We can also note that the tablecloth is white. This almost systematic code recalls the altar on which every celebration of the Eucharist, the symbol of the new alliance, takes place.